Rebooting Codesign

As AI dominates the conversation, we’re forgetting the power of deep research and codesign. We need to revive these powerful methods to enable meaningful, human design.

Codesign is becoming a lost practice — its rediscovery holds enormous potential.

TLDR

Codesign is vanishing from industry despite its ability to generate meaningful innovation through collaborative, participatory processes.

Its decline has been driven by overwhelming industry shifts toward evaluative UX research, big data, and AI being substituted for human engagement.

These shifts have left us drowning in data, yet ill equipped to envisage delightfully human products and services of tomorrow.

Reviving generative research and codesign can enable us to build long-term relationships with reflective users, engage diversity, and create genuinely new and meaningful concepts.

I intend to prove, not preach, the impact of community-powered codesign. That’s why I’m launching Micro Machines London 2025 - a diary study and codesign project that aims to uncover new insights and opportunities in the emerging field of micromobility.

From Codesign to UX and back again

I studied product design at university in the early 2000s, where I first saw how research could shape real-world products. At the time academic institutions like my own university’s Centre for Design Research, and specialist consultancies such as SeymourPowell Foresight, PDD, and Ideo sat at the boundary between research and industrial design.

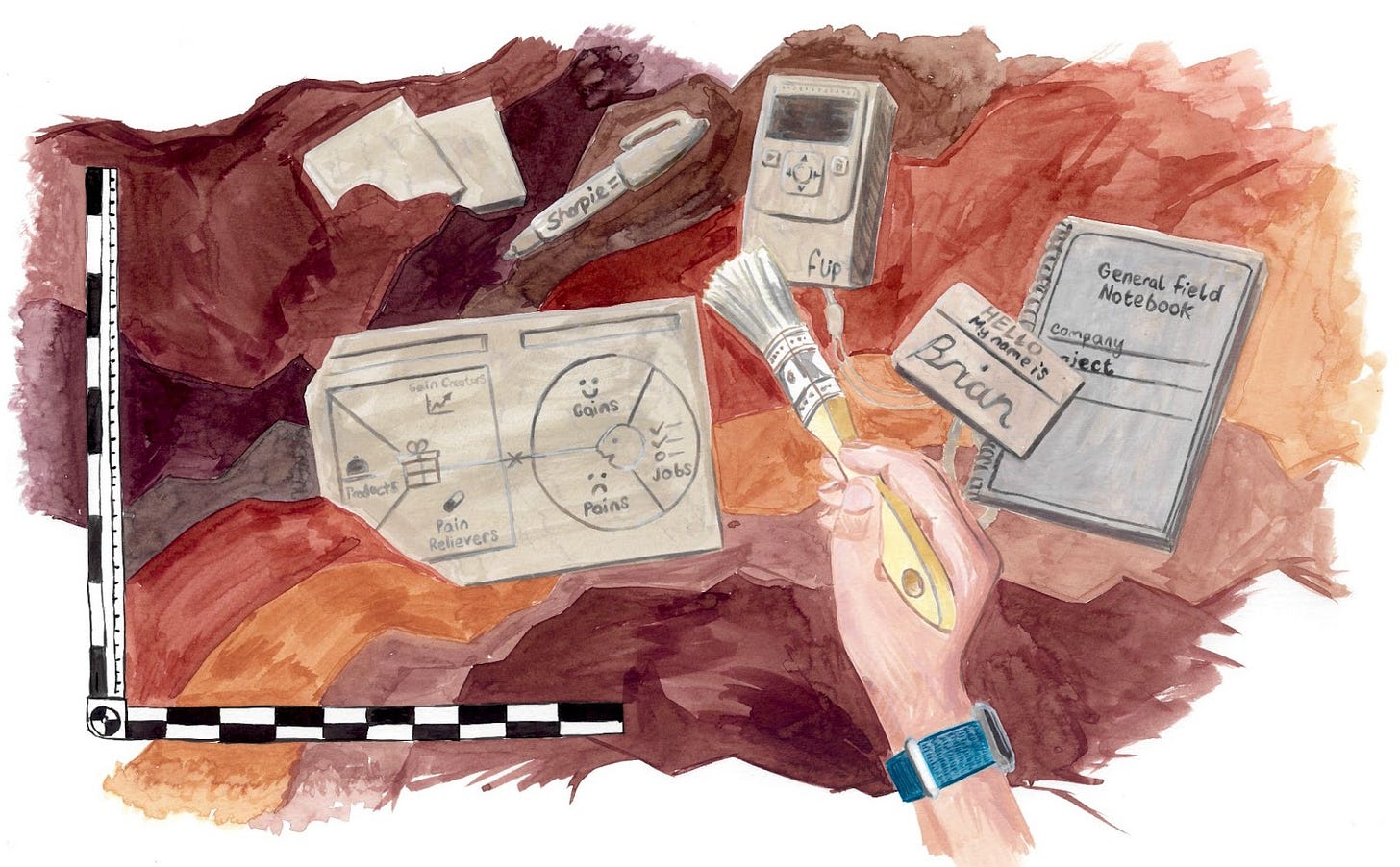

After graduating I went to work for research and innovation consultancy Sense Worldwide. We worked with global brands like Vodafone, and Nike, and would typically conduct ethnographic research outside the lab in the places people live, work and play. Projects would often build towards codesign workshops where articulate participants were brought together with cultural commentators and clients to define new opportunities. This was a form of research, but it was also highly collaborative and creative. It treated participants not as test subjects, but as sensitive interpreters to create powerful new ideas with.

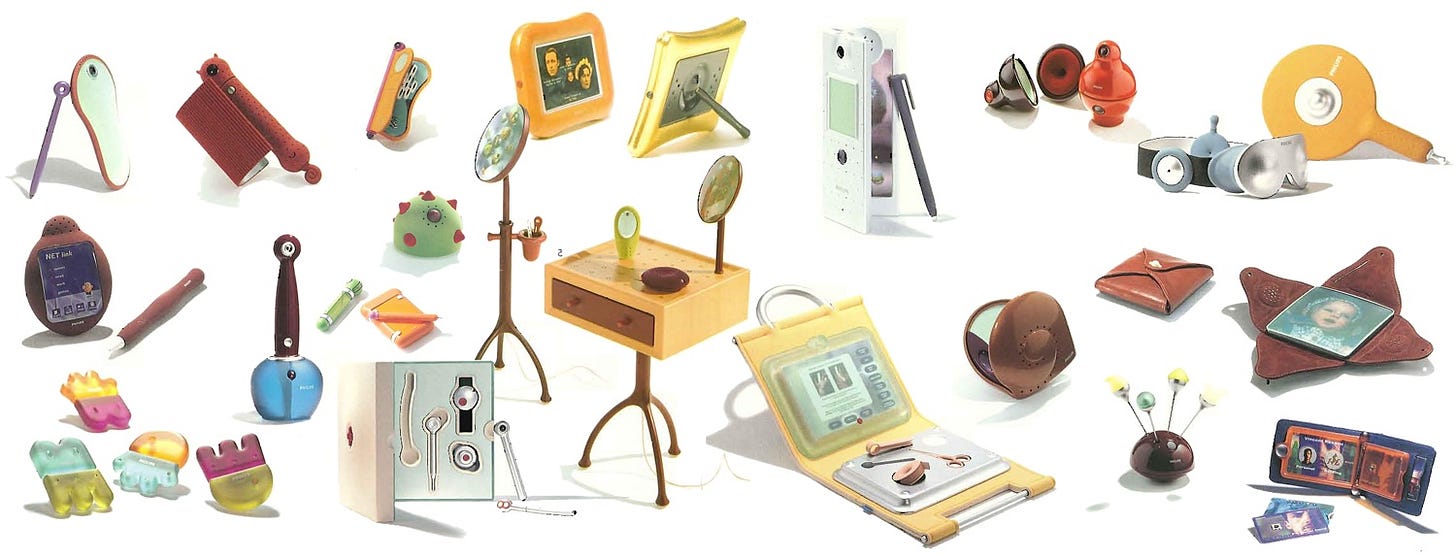

Philips’s Visions of the Future (1996) explored how everyday products might evolve, grounding its speculative concepts in deep research and cultural nuance.

The collaborative processes Sense embraced were not unique to them, rather they reflected a broader era in the history of user-centred innovation. I thought these ways of working would be part of our industry forever, but from today’s vantage point the period between the late 90s to the mid 2010s feels increasingly like a lost era. Surveying the wider landscape Intel’s People and Practices Group was led by a cultural anthropologist—Genevieve Bell, Nokia Design’s Insight & Innovation group worked extensively with anthropologists like Jan Chipchase, whilst Stefano Marzano, a design philosopher, deeply influenced by architecture, the humanities, and meaning-making served as Chief Design Officer at Philips between 1991-2011.

Roberto Verganti, Design Driven Innovation, 2006

A key thinker of the era is Roberto Verganti. In his publications ‘Design driven innovation’ (2006), and ‘Overcrowded: Designing Meaningful Products in a World Awash with Ideas’ (2017) Verganti articulated his thesis that the most radical innovations arose not from solving existing problems or asking users what they want, but rather from changing the meaning of products and services — an interpretive process he calls ‘design-driven innovation’. For companies looking to create meaningful innovation he discourages a market research led approach; asking users what they want, and advocates for one of deep and collaborative work with ‘interpreters’: individuals who have deep cultural or domain knowledge and can reinterpret existing products or behaviors in new ways. Engagement of interpreters creates strategic advantage for companies, enabling them to focus on coherence and quality, rather than volume of ideas.

Lego provides an example of this strategy in action. In the early 2000s, Lego saw children increasingly shift away from traditional toys toward digital entertainment and the brand’s attempts at diversification, such as theme parks and video games had not done enough to revive their fortunes. Rather than relying on traditional market research or internal brainstorming, Lego engaged interpreters in their field—adult fans, educators, designers, and technologists. Only some of these people were existing Lego buyers, but they were individuals who deeply understood the cultural and emotional significance of play, creativity, and building. They created the Lego Ideas platform, through which compelling concepts could be captured and developed with the original creators receiving royalties. This framework and flow of ideas helped reframe Lego not merely as a toy, but as a creative platform sparking imagination across generations.

There are many parallels between Verganti’s thinking and the codesign processes I have pursued throughout my career. Deep, generative research which builds toward codesign workshops are a powerful way of building a relationship with participants. Building the trust and creative confidence of participants along the way, they create an atmosphere where new ideas can flower. Unlike conventional market research the goal is not to exclusively target the average customer, but also to engage more niche groups such as the early adopters of new technologies. The theory behind this approach is that new ideas often emerge at the boundaries of present day experience, and the weak signals of future trends are already visible if we pay close attention.

Why are we leaving codesign behind?

Back in the early 2010s, I believed generative research and codesign were poised to flourish. Online technologies were evolving fast, making it easier than ever to run collaborative projects across time and distance. Yet, in hindsight, the mid-2010s marked not a rise, but the beginning of a decline.

I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on why these valuable ways of working faded from view. In short, I believe their decline stems from three major shifts in industry practice that, together, have acted to crowd out codesign and eroded trust in its value:

1. The Rise of Screen-Based UX and Agile Structures

As the 2010s progressed, research roles increasingly shifted from “design research” to “UX research.” This change reflected a narrowing of focus, often centered on optimising user flows within apps and websites, rather than exploring broader, long-term experiences across physical and digital touchpoints.

At the same time, many researchers found themselves embedded within agile product teams, where their work became tightly aligned with the near-term needs of shipping features. In this context, research naturally leaned toward evaluation - testing button placements, layouts, and messaging - rather than open-ended exploration or generative discovery.

Tools like A/B testing became popular because they offered speed, measurability, and clarity. And when used thoughtfully, they’re powerful methods. But in my experience working with digital teams, I’ve also seen them used too hastily, and applied to complex, multi-variable design decisions where the outcomes are ambiguous. When that happens, testing risks becoming a form of busy work, diverting energy from larger strategic questions.

None of these shifts are inherently negative. Agile teams and evaluative methods can be highly effective. The deeper concern is that they’ve become the dominant norm—sweeping like a tidal wave across organisations and obscuring the idea that research can also be used to ask open questions and explore new directions. In many companies, quickfire testing tools and big data now capture the imagination of leadership far more often than the human narratives that emerge from deep research.

2. Industry pushback against design thinking

In the late 2010s, a wave of critique emerged, often from professional designers, challenging the validity of design thinking and, at times, innovation processes more broadly. This backlash typically portrayed design thinking as a superficial exercise, where any stakeholder could be handed a stack of sticky notes and suddenly assume the role of the designer. Many saw this as a dilution of design craft and expertise.

There’s some truth in these concerns, particularly in how design thinking was sometimes applied in practice: with sticky-note workshops used as performative creativity. But this critique misses the original intent behind constructive, collaborative approaches. Consultancies like IDEO, who helped popularise design thinking, never proposed that designers be replaced. Rather, they aimed to widen the aperture of creative input and bring more people into the conversation, while still valuing deep design expertise.

As someone trained in industrial design, I hold a deep respect for the role of skilled designers. I also believe that codesign and participatory processes can exist in harmony with professional practice. It’s not a binary choice. When done well, these approaches enrich each other, broadening perspective without compromising craft.

3. The rise of AI

Since the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in late 2022, hype around large language models and conversational AI has reached fever pitch. As these technologies evolve it seems entirely likely that senior leaders may be inclined to lean on AI to play a similar role to the ones we might have looked to from codesign programmes in the past; namely the forecasting of future trends, or generation of new product concepts. The risks of recruiting AI to play these generative and interpretive roles are multiple. First AI models are trained on historic data and are effective at synthesizing what already exists, but are poor at surfacing emergent meanings, or radical cultural shifts. Perhaps most vitally today's online platforms present a powerful opportunity to engage and co-create with real, intelligent humans. Why let an algorithm speak for them?

Where does all this leave us?

We find ourselves sleepwalking into a world awash with data but starved of meaningful insight. User research has become increasingly instrumentalized - siloed within teams and focused on incremental optimisation. But human experiences unfold across a broader terrain. They’re not confined to an app’s messaging inbox or settings menu.

Siloed product teams are often predisposed to tinkering with the fine-grained details of interfaces, but less equipped to reinterpret or redefine compelling brand experiences.

The challenge is this: positive future brand experiences must be designed—not just described. That requires deeper insight into how people live, feel, and interact, as well as a closer partnership between research and design to bring desired experiences to life. A brand’s experience is ultimately judged in its delivery—not its promise.

At the same time, markets are becoming saturated with generic offerings. Brands know they must differentiate through experience. Many now declare themselves ‘experience-led,’ yet this ambition often lacks substance without a clear understanding of what experiences people truly want. Leadership vision statements alone won’t get us there. We need a sustained flow of ideas and understanding from outside the company.

Evaluative UX research isn’t built to serve that purpose. Great customer experiences aren’t created by ticking off feature lists or tweaking buttons—they’re composites of what happens on and offline, across time, and are judged by how they feel at the point of use.

So, what kinds of practice can fill this gap? How do we define meaningful product and service innovations, and what can we gain from generative codesign?

Verganti’s conception of design-driven innovation has been a major influence on my thinking. But I diverge from his model in one key way. While Verganti focuses on collaboration with visionary stakeholders inside companies, my experience suggests that some of the most insightful interpreters are also the product’s real-life users.

That’s why my approach centres on building longer-term partnerships with reflective, creative users through durational, participatory research—often via diary studies. Verganti cautions against asking users what they want or prompting them to react to pre-baked propositions—an approach rooted in the assumptions of market research. I agree. But what matters most is how we engage participants. I treat them not as test subjects, but as strategic partners. In the projects I’m most proud of, there’s a clear line between a participant’s deep insight and the emergence of a compelling new concept which addresses it.

The pillars of codesign success

In my experience, successful codesign rests on four essential pillars:

1. Find reflective people

It’s not just about finding users who fit the brief, like seasoned e-bike riders in London - but also those who bring curiosity, thoughtfulness, and depth. These individuals may not always be the most articulate on paper, but they show depth through thoughtful responses and original thinking. A well-placed open question or a short video prompt can reveal who’s ready to think beyond the obvious. These are your interpreters in the making.

2. Use the right platforms

Digital tools now make it easy to run rich, durational research. Diary study platforms, for example, let us see how people engage with products in real time, in the context of their real lives. Over days or weeks, participants build confidence and the insights deepen. These platforms aren’t just for observation; they’re for creative preparation, priming participants for later collaboration.

3. Engage with imagination

Great engagement isn’t just about asking the right questions - it’s about sparking the right kind of thinking. We should pose prompts that invite genuine reflection and lateral thinking, and share our own provocations and inspiration along the way. A simple project blog or regular community update can feed the fire, building momentum and mutual investment.

4. Centre diversity

To design inclusive, meaningful experiences we need to learn from people who navigate the world differently - from other cultures, abilities, neurotypes, and perspectives. Their insights stretch our assumptions and expand what’s possible. This isn’t about ticking a box, it’s about enriching the work. Engaging diverse voices is a privilege, and a strategic advantage.

Putting it all together: Micro Machines London

Micro Machines London: A research and codesign project focused on micromobility services.

By now, I hope it’s clear: I believe deeply in codesign—not just as a method, but as a mindset for unlocking meaningful innovation. The kind of research that energises me isn’t about validation or marginal gains. It’s about creative interpretation, mutual exchange, and shaping entirely new value propositions through collaboration with real people.

To put these principles into practice, I’ve launched Nourish Codesign—a new consultancy dedicated to community-powered innovation—and our first proof-of-concept project: Micro Machines London.

This three-week study will engage 15 reflective, articulate Londoners: a mix of e-bike owners and regular users of rideshare platforms. Through diary-based research and follow-up codesign workshops, we’ll explore what micromobility means to people now, and where it could go next. Participants will share their experiences and ideas via a diary study platform, and be guided by a live project blog to spark imagination and conversation.

This project brings together everything I care about: working with thoughtful people, blurring the lines between physical and digital experiences, and uncovering insights that help shape not just better products, but better futures. Most of all, it’s about proving through action and not words, that when people are treated as strategic partners, not test subjects, the results are richer, more human, and far more impactful.

I embark on this project in a spirit of openness and transparency. If everything I’ve said about the value of generative research and codesign holds true, then the insights and ideas that emerge should speak for themselves—enabling clients to do what yesterday’s research couldn’t, or could only do in limited ways:

Transport regulators like TfL or LA Metro will be able to identify friction points across neighbourhoods, prioritise infrastructure upgrades, and deploy smart nudges to shift travel behaviour.

Experimental product teams in Google, Apple and Xiaomi can surface emerging opportunities in personal mobility and digital payment, and translate them into prototypes.

Rideshare platforms like Lime or Forest will be equipped to refine service touchpoints, improve retention, and design the next generation of vehicles around lived experience—not just usage metrics.

Micro Machines London runs 26th May - 15th June 2025

Want to take part? Learn more and register your interest at: www.nourishcodesign.com

Curious about how generative research and co-creation could help your organisation innovate? I’d love to chat. Drop me a line at: james@nourishcodesign.com